By Mustafa J. Salem, Mabrouk T. Busrewil and Khaled M. Oun.

Tripoli, 3 July 2103:

Waw An-Namus, one of the most beautiful scenes in the Libyan Sahara,

lies about 240 kilometres east of the oasis of Tmassah and about a 120

kilometres east of Waw Al-Kabir. This beautiful volcano is located at

the southern edge of the major Al-Haruj volcanic field (see Figure 3 for its location).

Waw An-Namus, one of the most beautiful scenes in the Libyan Sahara,

lies about 240 kilometres east of the oasis of Tmassah and about a 120

kilometres east of Waw Al-Kabir. This beautiful volcano is located at

the southern edge of the major Al-Haruj volcanic field (see Figure 3 for its location).

Due to the presence of fresh water at this remote volcano and

throughout the long history of desert caravan travel, Waw An-Namus was

always an important watering point for the caravans en route from Waw

Al-Kabir to Rebiana and Al Kufrah oases further southeast in Libya.

Due to the presence of fresh water at this remote volcano and

throughout the long history of desert caravan travel, Waw An-Namus was

always an important watering point for the caravans en route from Waw

Al-Kabir to Rebiana and Al Kufrah oases further southeast in Libya.

This scenic volcano remained unknown to the outside world until it was reported by Karl Moritz von Beurmann (1862) and Gerard Rohlfs (1881), although they never visited the volcano. Probably the first European to visit this volcano and report it was a Frenchman, Laurent Lapierre (1920). Lapierre was a military officer who was captured in combat and taken in captivity to Kufra via Waw Al-Kabir and Waw An-Namus, and so had the opportunity to report his adventure after his release a few years later.

About eleven years later an Italian geologist, Ardito Desio, reached Waw An-Namus during his famous long camel journey. On his geological expedition, Desio also visited Jalu, Maradah, Waw Al-Kabir, Tmassah and Kufra and published a geological description of the volcano for the first time in 1935.

After the Second World War, several scientists visited the volcano, including the geographer Nikolaus Benjamin Richter who undertook several trips to the volcano and published a book on his journey to the area in 1960. He first visited Waw An-Namus during the war as a member of the Sonderkommando Dora, the surveying group attached to Rommel’s Deutsche Afrikakorps.

Since that time, and as the Libyan government began awarding petroleum concessions in Libya, several geologists, geophysicists and tourists have visited Waw An-Namus, either to explore the adjacent areas or because they were attracted by descriptions of the volcano. In 1962, the Petroleum Exploration Society of Libya (PESL) included a reconnaissance flight over this volcano during its excursion to Tibisti-Chad (Figure 5).

A few years later, in1966 Italian geologist Angelo Pesche published a concise geomorphologic description of the volcano.

A few years later, in1966 Italian geologist Angelo Pesche published a concise geomorphologic description of the volcano.

In the last two decades, Waw An-Namus has became one of the main destinations for most tourists who visit the Libyan desert in general and the Fezzan region in particular.

The volcano

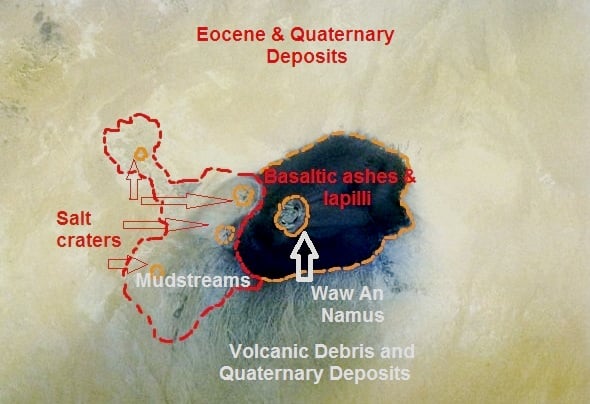

The surrounding terrain is very flat and, when approaching, the volcano can only be recognised by the black ash-fall and lapilli tuff deposits which surround the collapsed depression for a distance of about 10 kilometres, in stark contrast to the light-coloured sand and Eocene carbonates that are exposed in the adjacent area surrounding it (Figures 4 and 7).

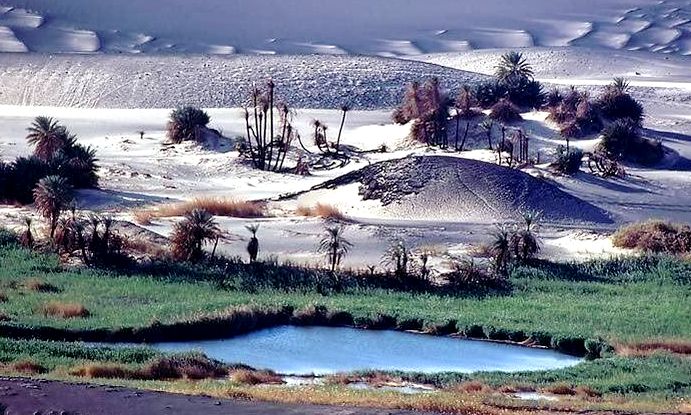

Then unexpectedly, one arrives at the rim of the caldera and is overwhelmed by the incredibly beautiful scene in the middle of the desert; the caldera is about four kilomtres in diameter and about 100 metres deep. Surrounding the central volcanic cone, at the bottom of the collapsed depression, there are three main brackish lakes and a few smaller ones, some of which are brownish in colour. These are surrounded by tall reeds (Phragmites) and scattered wild date palms, which add to its beauty (Figure 6).

A common enough phenomenon in the Sahara is the occurrence of reasonably potable water close to, and at nearly the same elevation as, salt lakes. This scarce source of water feeds the lakes and was also used by travellers in the old days. Due to the lack of continuously recorded observations, the magnitude of oscillations of the water level is unknown. In earlier years, the level of the lakes appeared to be somewhat stable, but in recent years it has been noticed that during the summer months, when the rate of evaporation increases, some parts of the western lakes dry out forming a white salt crust around the rim of the lake, which may indicate a reduction in the amount of water feeding the lakes (Figure 2).

No associated lava flows are present at the crater, but the volcano

itself is built almost entirely of ash and lapilli-sized cinders with a

greatly reduced number of volcanic bombs and blocks ejected around the

vent during Strombolian eruptions. It may represent a vent of explosive

eruption that rapidly transported a mixture of magma and accidentally

caught deep-seated lherzolite nodules without appreciable residence time

in a crustal magma chamber or from a reservoir at great depths.

No associated lava flows are present at the crater, but the volcano

itself is built almost entirely of ash and lapilli-sized cinders with a

greatly reduced number of volcanic bombs and blocks ejected around the

vent during Strombolian eruptions. It may represent a vent of explosive

eruption that rapidly transported a mixture of magma and accidentally

caught deep-seated lherzolite nodules without appreciable residence time

in a crustal magma chamber or from a reservoir at great depths.

Bordering the volcano on the west are a few salt craters with mud streams flowing from them in a northerly direction (Figure 4).

Petrographic descriptions of the basalt from Waw An-Namus were undertaken by Engel and Bausch (1962) on samples collected from the volcano and show that the rock is characterized by xenocrysts of forsterite and bronzite embeded in a fine-grained to cryptocrystalline groundmass consisting of plagioclase microlites, olivines, aegirine-augite granules and glass. Other geochemical and mineralogical analyses for the volcano were also published, for the first time, by M.T. Busrewil and M.J. Wadsworth in 1983. In their publication these authors showed that the rocks are basanites with a strong alkaline character. Moreover the authors indicated that the mineralogical composition of lherzolite xenoliths from the volcano is broadly similar to other comparable worldwide occurrences of xenoliths.

The mantle-derived nodules, up to fist size with individual olivine granules as large as 5 mm in diameter, are prominent near the rim of the caldera. Unfortunately, however, many of these semi-precious minerals have already been picked up and removed by visitors to the volcano.

In 2012, Jacques-Marie Bardintzeff and others published a comprehensive geochemical and mineralogical study about the volcano. They dated the Waw An-Namus volcano for the first time indicating that the age of the cone is 0.2 Ma (200,000 years old). The chemistry of the analysed specimens was reported to be under–saturated foidite, representing the most extreme compositions among Libyan and Tibestian lavas. Compared to the other volcanic fields in Libya, the Waw An-Namus volcano is believed to have been active during the effusion of the last episode of Al Haruj, or less likely at much later time.

Most tour operators insist on driving their clients down the collapsed depression to picnic near the lakes and this has impacted not only the soft surface of the volcano but also damaged its fragile habitat. A few years ago, some careless visitors caused a fire in the eastern foliage of the oasis, burning a large area of it including some date palms (Figure 8).

It is imperative that vehicles be prevented from driving down the caldera. Visitors should only be allowed to walk down, while their vehicles wait on the rim.

In the very near future this volcano must be protected by law and visits to it will need to be regulated and closely controlled.

Tripoli, 3 July 2103:

Figure

1. Panoramic view of Waw An-Namus, with the centre cone in the middle

of the large volcanic crater (caldera) formed by roof collapse above the

underlying magma chamber. The volcano is surrounded by brackish lakes

and vegetation including some date palms. The dark colour indicates the

accumulated tephra mantling the surrounding area (Photo courtesy of Toby Savage).

Figure

2:Waw An-Namus volcano with the lakes on its western side. Notice the

white salt crust around the lakes indicating a reduced water supply in

recent times. Smaller lakes on the far side are brownish in colour (Photo courtesy of Toby Savage).

Figure

3: Satellite image showing location of Waw An-Namus in south-central

Libya, at the southern edge of the major Al Haruj volcanic field.

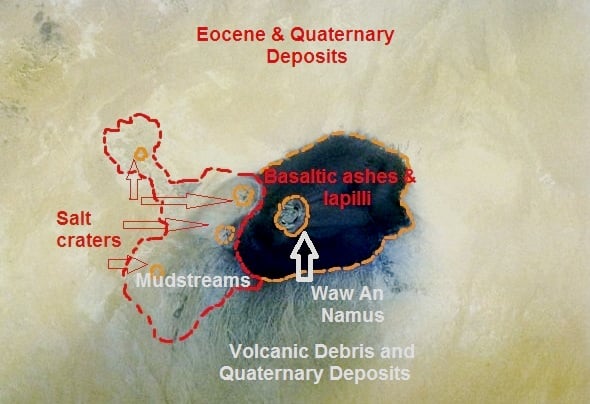

Figure

4: Sketch map of the area of Waw An-Namus, indicating the location of

the volcano in relation to salt craters, mud streams and volcanic ash

debris. (Figure modified from Angelo Pesce,1966. Image –Space Shuttle 1992)

This scenic volcano remained unknown to the outside world until it was reported by Karl Moritz von Beurmann (1862) and Gerard Rohlfs (1881), although they never visited the volcano. Probably the first European to visit this volcano and report it was a Frenchman, Laurent Lapierre (1920). Lapierre was a military officer who was captured in combat and taken in captivity to Kufra via Waw Al-Kabir and Waw An-Namus, and so had the opportunity to report his adventure after his release a few years later.

About eleven years later an Italian geologist, Ardito Desio, reached Waw An-Namus during his famous long camel journey. On his geological expedition, Desio also visited Jalu, Maradah, Waw Al-Kabir, Tmassah and Kufra and published a geological description of the volcano for the first time in 1935.

After the Second World War, several scientists visited the volcano, including the geographer Nikolaus Benjamin Richter who undertook several trips to the volcano and published a book on his journey to the area in 1960. He first visited Waw An-Namus during the war as a member of the Sonderkommando Dora, the surveying group attached to Rommel’s Deutsche Afrikakorps.

Since that time, and as the Libyan government began awarding petroleum concessions in Libya, several geologists, geophysicists and tourists have visited Waw An-Namus, either to explore the adjacent areas or because they were attracted by descriptions of the volcano. In 1962, the Petroleum Exploration Society of Libya (PESL) included a reconnaissance flight over this volcano during its excursion to Tibisti-Chad (Figure 5).

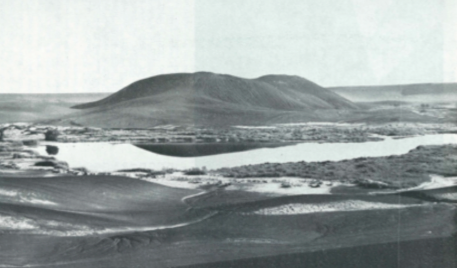

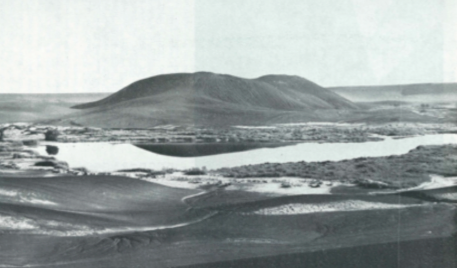

Figure

5: Historic view of Waw An-Namus published by A. Pesce in 1966 as part

of a publication by the Petroleum Exploration Society of Libya. The

western lake appears in the foreground.

In the last two decades, Waw An-Namus has became one of the main destinations for most tourists who visit the Libyan desert in general and the Fezzan region in particular.

The volcano

The surrounding terrain is very flat and, when approaching, the volcano can only be recognised by the black ash-fall and lapilli tuff deposits which surround the collapsed depression for a distance of about 10 kilometres, in stark contrast to the light-coloured sand and Eocene carbonates that are exposed in the adjacent area surrounding it (Figures 4 and 7).

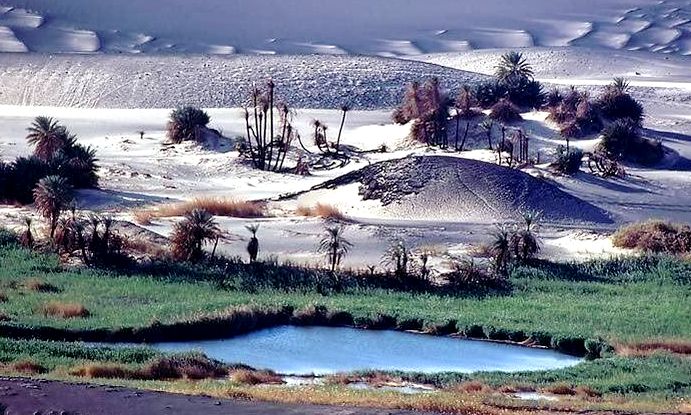

Then unexpectedly, one arrives at the rim of the caldera and is overwhelmed by the incredibly beautiful scene in the middle of the desert; the caldera is about four kilomtres in diameter and about 100 metres deep. Surrounding the central volcanic cone, at the bottom of the collapsed depression, there are three main brackish lakes and a few smaller ones, some of which are brownish in colour. These are surrounded by tall reeds (Phragmites) and scattered wild date palms, which add to its beauty (Figure 6).

A common enough phenomenon in the Sahara is the occurrence of reasonably potable water close to, and at nearly the same elevation as, salt lakes. This scarce source of water feeds the lakes and was also used by travellers in the old days. Due to the lack of continuously recorded observations, the magnitude of oscillations of the water level is unknown. In earlier years, the level of the lakes appeared to be somewhat stable, but in recent years it has been noticed that during the summer months, when the rate of evaporation increases, some parts of the western lakes dry out forming a white salt crust around the rim of the lake, which may indicate a reduction in the amount of water feeding the lakes (Figure 2).

Figure 6: Close-up view of the centre cone in the background and tall reeds surrounding the lake in the foreground (Photo courtesy of Toby Savage)

Bordering the volcano on the west are a few salt craters with mud streams flowing from them in a northerly direction (Figure 4).

Petrographic descriptions of the basalt from Waw An-Namus were undertaken by Engel and Bausch (1962) on samples collected from the volcano and show that the rock is characterized by xenocrysts of forsterite and bronzite embeded in a fine-grained to cryptocrystalline groundmass consisting of plagioclase microlites, olivines, aegirine-augite granules and glass. Other geochemical and mineralogical analyses for the volcano were also published, for the first time, by M.T. Busrewil and M.J. Wadsworth in 1983. In their publication these authors showed that the rocks are basanites with a strong alkaline character. Moreover the authors indicated that the mineralogical composition of lherzolite xenoliths from the volcano is broadly similar to other comparable worldwide occurrences of xenoliths.

The mantle-derived nodules, up to fist size with individual olivine granules as large as 5 mm in diameter, are prominent near the rim of the caldera. Unfortunately, however, many of these semi-precious minerals have already been picked up and removed by visitors to the volcano.

In 2012, Jacques-Marie Bardintzeff and others published a comprehensive geochemical and mineralogical study about the volcano. They dated the Waw An-Namus volcano for the first time indicating that the age of the cone is 0.2 Ma (200,000 years old). The chemistry of the analysed specimens was reported to be under–saturated foidite, representing the most extreme compositions among Libyan and Tibestian lavas. Compared to the other volcanic fields in Libya, the Waw An-Namus volcano is believed to have been active during the effusion of the last episode of Al Haruj, or less likely at much later time.

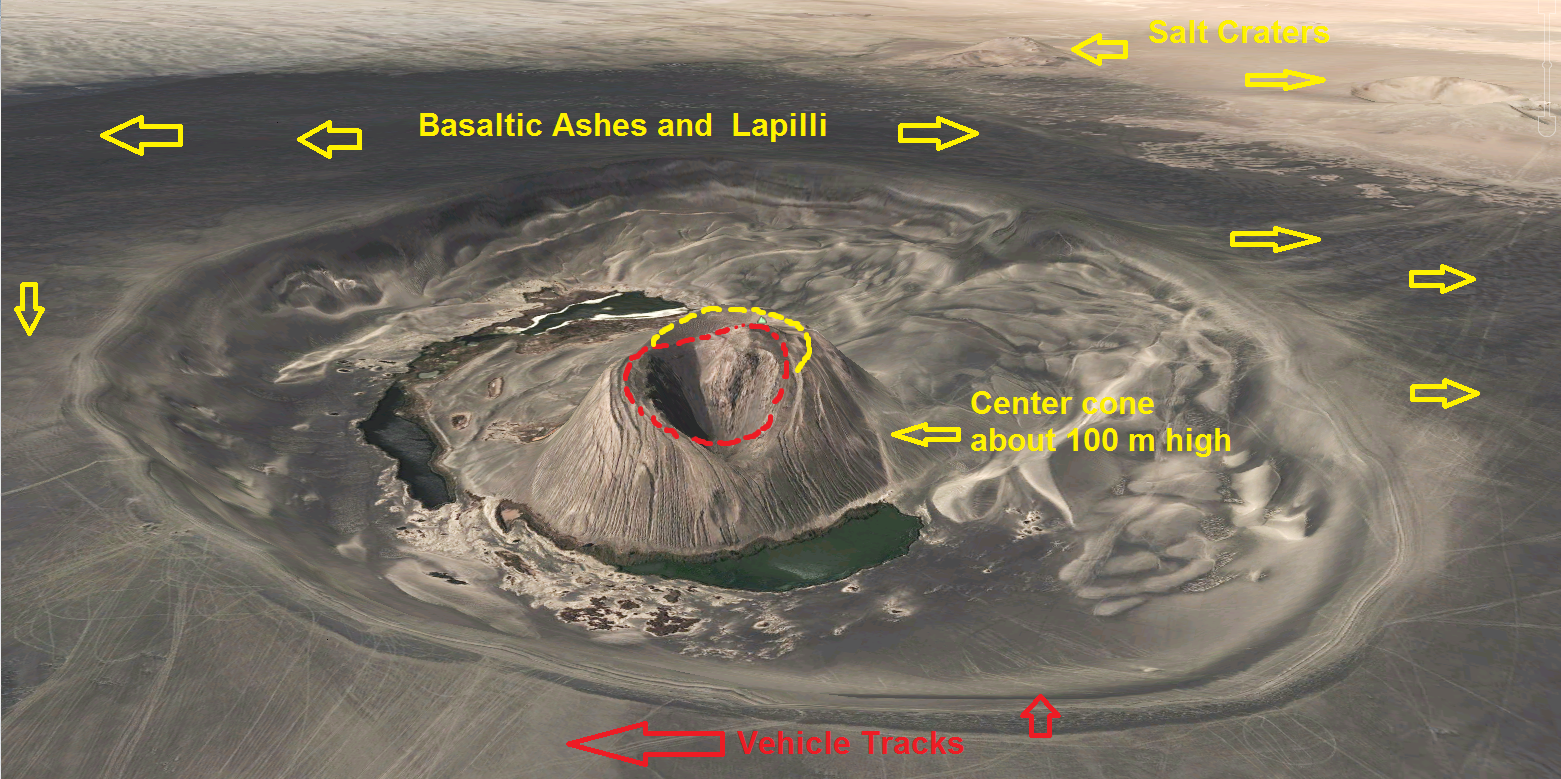

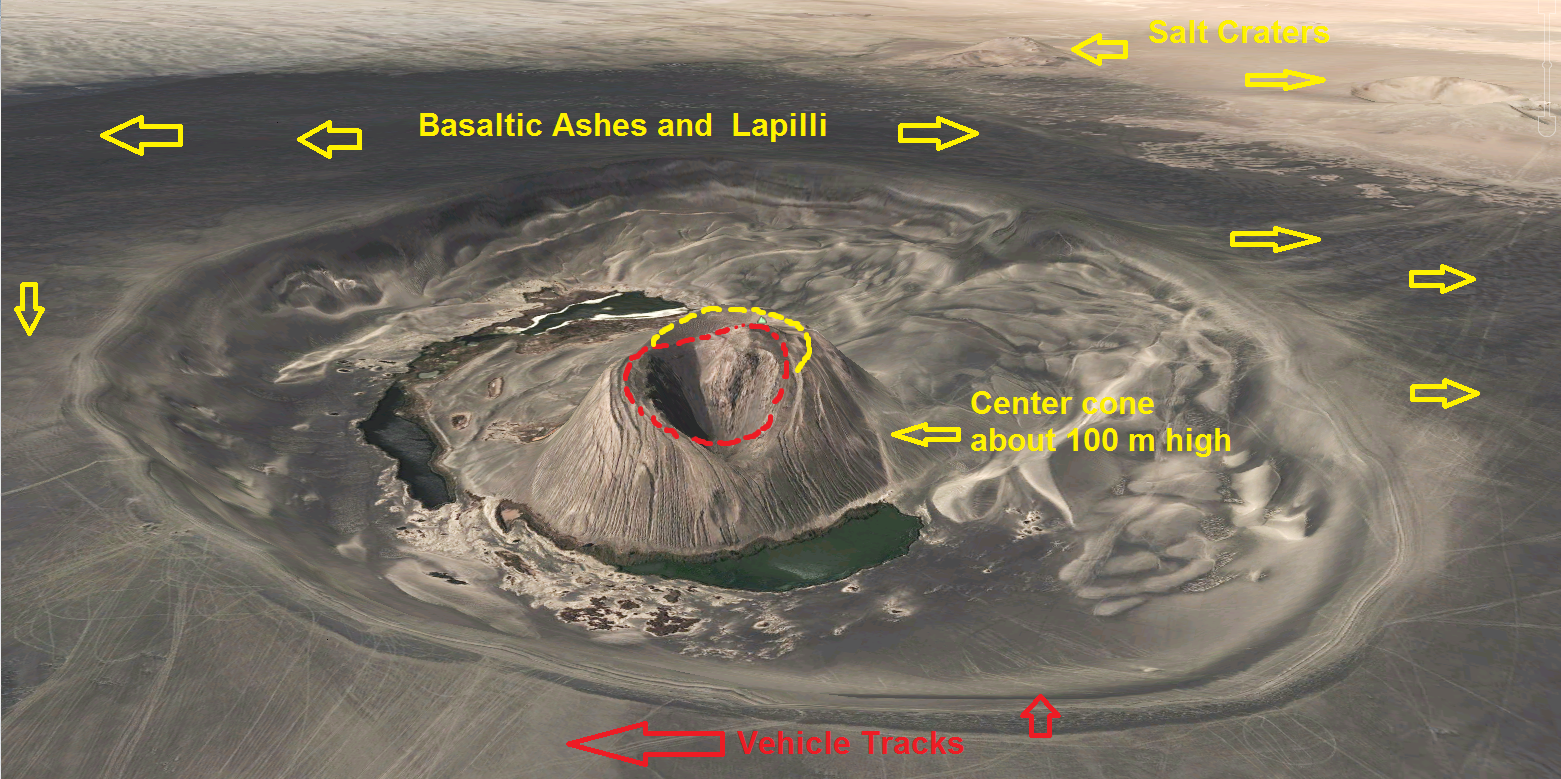

Figure

7: Satellite image of Waw An-Namus showing various features of the

volcano. At the top right note two of the salt craters. Inside the

caldera the volcano records two repetitive episodes of growth and

destruction. The inner cone may represent a relatively late

manifestation of a major explosive eruption (phreatomagmatic) in the

area. The numerous vehicle tracks indicate that some visitors drive down

to the centre of the volcano, while others circle the rim of the

depression

The volcano as a tourist attraction

Most tourists who visit the Libyan desert

make sure to include in their itinerary a visit to Waw An-Namus even for

just a short time. Perhaps it is the beauty of the volcano with its

magnificent depression that is rich in foliage and with the salt lakes

of various colours that are the reason for its attraction and fame.

With the increasing number of visitors in the last 20 years, this

small ‘oasis’ has experienced negative impacts on the landscape as well

as on its rare fauna and flora.Most tour operators insist on driving their clients down the collapsed depression to picnic near the lakes and this has impacted not only the soft surface of the volcano but also damaged its fragile habitat. A few years ago, some careless visitors caused a fire in the eastern foliage of the oasis, burning a large area of it including some date palms (Figure 8).

It is imperative that vehicles be prevented from driving down the caldera. Visitors should only be allowed to walk down, while their vehicles wait on the rim.

In the very near future this volcano must be protected by law and visits to it will need to be regulated and closely controlled.

Figure

8: Eastern side of Waw An-Namus volcano with a small part of the

eastern lake in the foreground. Burned reeds and date palms can be seen

in the background. These rare flora were burned as a result of

negligence by some visitors, and the authorities need to prohibit the

lighting of any fires in this fragile area.

libya herald

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق